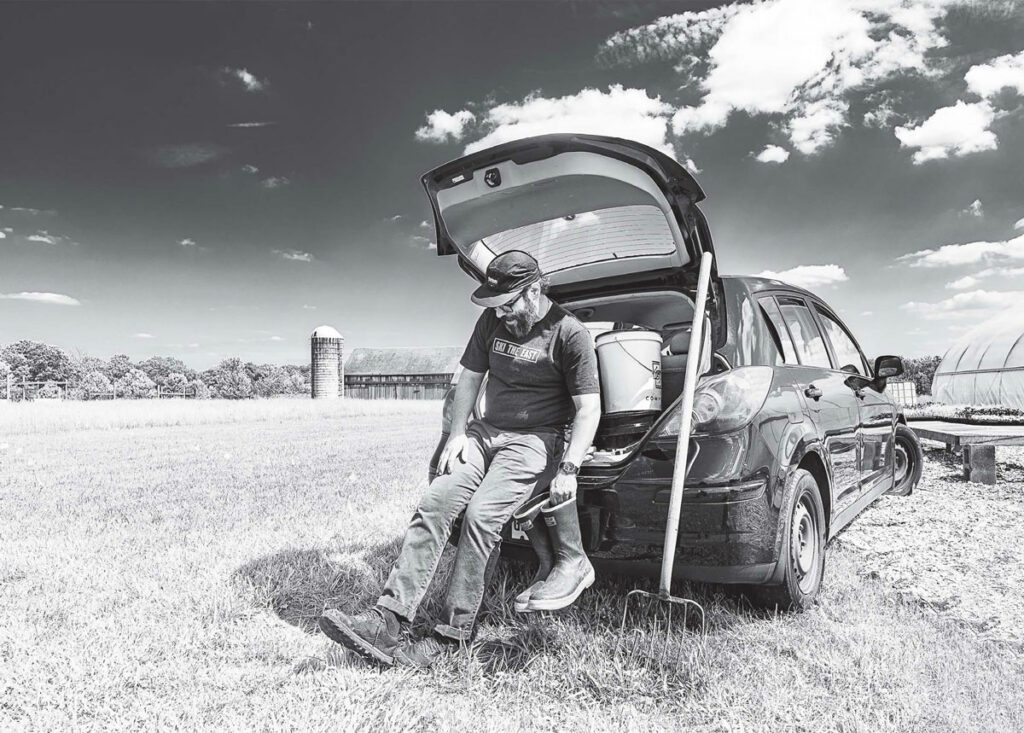

By Michael Joyce | Photos By Roberto Quezada-Dardón

ON A FIERCELY COLD, GRAY JANUARY MORNING IN 2023, I found myself sitting atop a very stubborn tractor that despite my best efforts did not want to start up. I wasn’t surprised. The temperature was nearly freezing and the rain was relentless. The wind was whipping up and over the exposed plateau where the farm sits, sending a chill up my spine.

After much pleading, the old tractor finally shuddered to life, obviously annoyed at having been awakened under such conditions. With numb fingers, I cinched the hood of my rain parka even tighter and jammed the tractor into gear. It lurched forward and, despite the rain pelting my face, I smiled. I smiled because I was genuinely happy, moving around piles of dirt in the dead of winter.

But how did I get here? I spent two decades dedicated to cooking; my life revolved around it, or you could say within it. It defined me. I had the type of dedication that unfortunately left my health and well-being neglected. For a long time, I soldiered on, pushed through the pain, and pretended I was fine. But I desperately needed a change.

The First Pivot: Gardening

Rewind to February 2020, when I was working as the chef de cuisine at a very popular restaurant in Center City, Philadelphia. It was the culmination of a long, hard culinary journey. I was finally making a decent salary, but I was far from happy. I had decided it would be my last restaurant job, but I didn’t know what would come next. I’d always daydreamed of a life outside of kitchens, making an honest living on a farm, growing food, and being a responsible steward of the land. As a chef, I’d always sought to align myself with the farming community; I’d worked for chef Dan Barber at Blue Hill, a top-notch restaurant in New York with its own working farm. You couldn’t get much closer to your ingredients than that. But a career change to straight-up farming in my 40s just seemed insane.

But life had other plans for all of us when the pandemic hit in spring 2020. During those first confusing weeks, the restaurant I worked for let me go. Restaurants gave me purpose and with that forcibly removed, I felt lost. I turned to my home kitchen, and started baking bread, fermenting kimchi, brewing kombucha, and making every meal for my little pod of me, my wife, Alix, and brother-in-law. I transformed our tiny South Philly concrete patio into a garden, repurposing free pallets into planter boxes. And I sprouted and planted everything I could get my hands on. Avocado pits, scallion bottoms, and a towering anise hyssop all found their way into my odd little lockdown garden. I didn’t know how to relax.

It’s not a huge surprise that I gardened through the pandemic; that seed had been quietly planted in me as a child. Some of my earliest and happiest memories involve working in the garden with my parents. Those beautiful, gnarly fruit trees, beefsteak tomatoes so big and juicy, peas so sweet and crunchy. And those Concord grapes that would stain my mouth and hands purple. My dad was always working on some project in the garden; my mom, picking tomatoes for BLTs or tomato sauce.

As a student of the Rodale philosophy, my dad built compost bins based on the classic “Lehigh bin” designed by J.I. Rodale. We would fill them up with the seemingly endless supply of leaves that would fall in our yard. I was always raking leaves. I hated it. Initially, I didn’t understand what my father already knew. Those bins in the back corner of our yard both confused and intrigued me as a child. They would steam all summer long, emitting a strange and intoxicating aroma while they broke down into the most beautiful soil, as if by magic. It would be years (and all these career pivots) before I could conceive of farm to table composting.

The Second Pivot: Gardening to Farming

During that first pandemic summer, Alix and I started visiting Plowshare Farm in Bucks County to escape the city and get outside. We would walk the farm, pick strawberries, and talk with the owner, the affable Teddy Moynihan. I began to feel more comfortable outside the restaurant universe. The idea of farming was starting to seem more plausible.

Around this time, another recovering chef friend, Will, had started working at Flocktown Farm in Pittstown, New Jersey. They were hiring for a job that required skills I possessed, honed by a lifetime of working in kitchens: wash barn manager.

Just three months after being laid off, I started working at Flocktown, a very large, organic home-delivery CSA farm. I was electric with excitement, but also full of apprehension and anxiety. (Imposter syndrome is real.) I soon found out that farm crews are very similar to the ragtag group of weirdos I had come to find kinship within restaurants. And being the wash barn manager was just like running a kitchen: receiving produce, washing vegetables, and organizing a walk-in. The biggest difference? You could drive a big ol’ John Deere tractor right down the middle of my new walk-in!

After one season at Flocktown Farm and a grueling commute, Alix and I decided to leave our South Philly row home and move back to the Lehigh Valley, where we both grew up. I worked out another full season at Flocktown, but I was starting to feel nostalgic for kitchen work when my old friends Erin Shea and Lee Chizmar serendipitously offered me a lifeline at their restaurant, Bolete, where I had worked a decade earlier. Next thing you know, I was helping at their newer spot, Mister Lee’s Noodles, forming dumplings and slicing mountains of scallions. The quiet of early morning prep work in an empty kitchen can be magical, similar to solitary predawn farm labor.

The Third Pivot: And Back to the Kitchen…

After a few months, Lee asked me to come on as the chef at Bolete and help them to reopen after the pandemic. I was excited but apprehensive. I wasn’t sure if I was ready for that life again. At about the same time, I also started working at Plowshare on my days off, preparing beds for planting or staking tomatoes. Teddy is a fervent teacher of all those sustainable farming practices I had been learning about over the years. Composting plays very heavily into the philosophy behind Plowshare and was often a familiar topic of discussion while picking beans.

One day at Bolete, I was receiving an order from another longtime farmer friend, Jeff Frank of Liberty Gardens in Coopersburg. Somehow, the conversation moved to composting and Jeff told me that food waste rotting in landfills is one of the largest sources of methane gas production. It’s bigger even than the methane produced by cows.

As someone greatly concerned about our environment and the amount of waste that kitchens produce, I couldn’t stop thinking about this for weeks. It rattled around in my head until one day at Bolete, while throwing out a bowl of onion skins, it hit me: We need to compost all our food scraps!

Finally: Farm to Table Composting

The next day, I went out and bought five 5-gallon buckets with the intent of transporting our kitchen scraps to Plowshare’s compost pile. I had no idea my kitchen crew would latch onto this with such enthusiasm. Even servers started saving spent coffee grounds, one of the most beneficial things to compost. Our pastry chef, Amy, would fill up an entire bucket with just eggshells, another rock-star ingredient. Five buckets soon grew to 10 and my little Nissan Versa quickly reached its max capacity (and became a bit smelly, too), as one compost pile at Plowshare quickly became four larger piles.

As my composting journey continued, I became even more fascinated by it. I felt a deeper connection with my father, who had passed a few years earlier. Memories of raking leaves and the steaming compost piles came flooding back. I remembered that those leaves I hated so much from my childhood contained tons of nutrients and minerals necessary to create that black gold.

Every week for an entire year, I collected as much compostable food waste from Bolete as I could fit in my hatchback and drove it to Plowshare. I didn’t know if this experiment in what’s basically farm to table composting would work. The weather (or the farm machinery) often wasn’t agreeable during these early morning excursions, but I genuinely enjoyed the task. Watching the transformation was humbling.

The recipe is easy enough: four parts browns (leaves) to one part greens (kitchen food scraps). I love a good recipe and a good ratio even more. Mixing browns and greens is not unlike mixing bread dough. Keep it at the proper temperature, add the right amount of moisture, and turn every so often. Sounds familiar.

It worked. Those piles of kitchen scraps and decomposing leaves broke down into the most beautiful, dark soil. Warm and crumbly. And the smell! Sweet with a pleasantly deep earthy aroma. It still feels every bit as magical as it did all those years ago.

These days, I’m pretty happy. I often joke that composting saved me but there is some real truth to it. I never planned on jumping back into full-time restaurant work; I didn’t feel like I had anything left to contribute to that conversation. Kitchen life doesn’t typically provide a sustainable path. It takes its toll.

Covid was terrible in a lot of ways, but it realigned my priorities. Cooking dinner at home for my family, spending time outside, and living in the present became the new priorities. I didn’t know I could live a life like this without completely abandoning food and farming. Composting became the bridge between the farm and the kitchen—and back again. •