STORY BY LENORA DANNELKE | PHOTOGRAPHY BY JOSHUA COATES

IN THE FOOD AND FARMING WORLD, we talk a lot about sustainability, often understood to mean things like how a crop is grown or how a farm manages the soil. But what is sustainable farming, really? For farmers, sustainability encompasses everything—it’s not just a buzzword or a slapdash label. It incorporates issues of how to handle waste, what to do with produce that’s not sellable. It addresses ways to manage your farmworkers and pay them, and how to work with Mother Nature when climate change has changed our USDA growing zone designation. Sustainable farming means farmers are worried about weather, profit margins, crop loss, and much more.

You’re with us so far, right? Let’s pull back the lens a bit further to consider how hard farmers work year round, much of it performing invisible labor, to prepare for the next season. (To wit: Do you think your farmers, much like your chefs, get much time off?) They are constantly reading, talking, investing, communicating, collaborating with other growers and producers—sharing ideas, methods, tools, and resources. To minimize waste, they’re looking for innovative ways to use and reuse every ounce of what they grow or raise. This often results in value-added products they can offer at their retail operations or market tables. New ventures and partnerships are carefully considered. But yet, farmers love what they do, and they do it with intention.

The irony? The very work of farming involves sustainability, but the work involved is not always sustainable for farmers. What are our farmers doing to ensure their businesses may thrive for generations to come? We talked to three growers in our region and Lenora tells us their stories.

—Carrie Havranek, editor

Apple Ridge Farm, Saylorsburg

“People talk about farm-to-table dining, but that’s not enough,” says Brian Bruno of Apple Ridge Farm. “Farmers should really be setting the table.” He pauses. “More farmers should own the table.”

Support for this bold declaration is evident in the economic and environmental sustainability of his farm, which boasts a wide diversity despite its modest seven-acre size.

Growing up on his family’s farm, Bruno, 42, never recognized what unique skill sets he was developing. While dreaming of getting off the farm and being “normal”—having days off and time to do things like watch TV—Bruno had an aha moment. He realized he had acquired a good work ethic, could fix things, and creatively approached problem solving. Prior to attending Penn State as an Environmental Resource Management major, he says he didn’t quite understand “how important the way we raise our food is to the earth.” Once the direct connection between industrial food production and damage to the environment became clear, he began to reconsider his career choice. In fact, while he was still in college, Bruno’s parents considered retiring and selling the farm. He objected, pleading, “Wait! Stop! This farm means everything to me!”

Developing multiple revenue streams and value-added products took place gradually; Bruno has the mind of an entrepreneur. “We believe in enterprise stacking; we do a little bit of a lot,” he says. Bruno’s farm, established in 2003, was founded on two acres of vegetable production. Later, pasture-raised chickens for eggs and meat were added.

Raising two batches of five pigs a year followed. The animals are housed in horse trailers with ramps and moved to different locales every four days. “We use them to clear fencerows and paddocks,” Bruno says. “They’re like little plows. They turn everything over.”

Sustainable Farming: The Produce

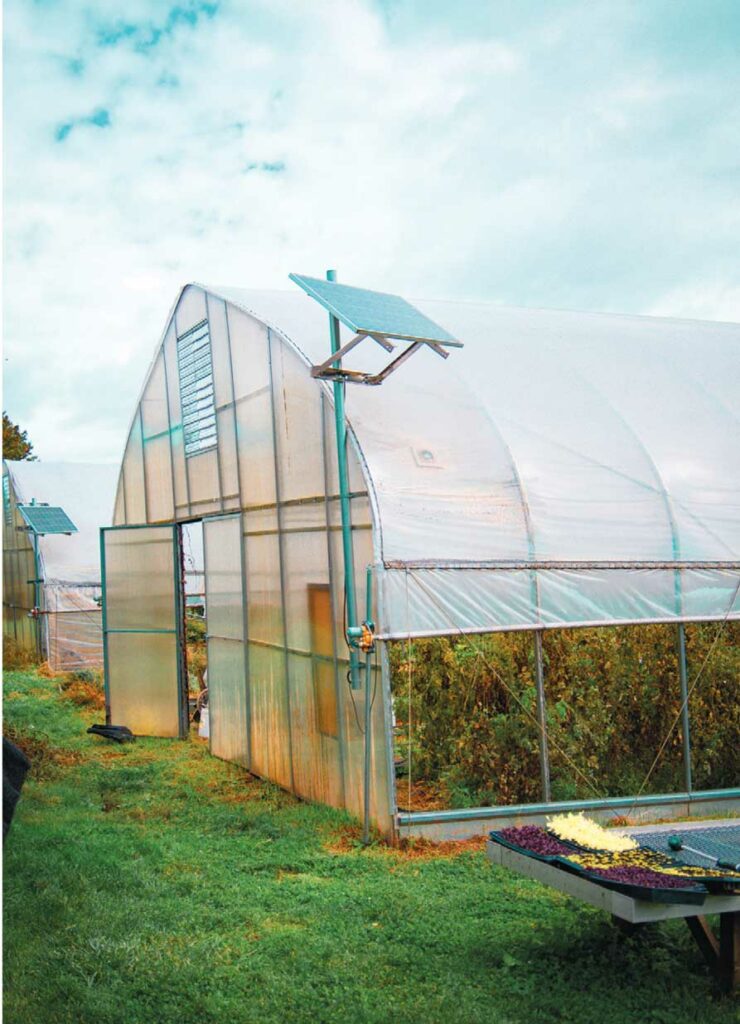

On the horticultural side, the farm currently has one heated greenhouse for starting seeds in spring, one mobile high tunnel on wheels, two caterpillar tunnels, and several knee-height hoop tunnels. They use a hydroponic system for growing microgreens and lettuce. The highly competitive Diversified Vegetable Apprenticeship program administered through PASA and implemented at Apple Ridge provides hands-on training for aspiring farmers; Bruno is an involved mentor. Successful participants are housed on-site in a three-bedroom farmhouse during their tenure, which may last up to two years.

In 2006, a disastrous 12-inch rainfall in a 24-hour period washed out half the garden. This calamity brought the realization that it was necessary to offer products that would balance out seasonal fluctuations. The next year, Apple Ridge turned the farmhouse’s summer kitchen into a small commercial kitchen, which was expanded in 2010 when they built their first wood-fired bread oven. Their baked goods found immediate success at farmers markets. In addition, Bruno’s no-waste philosophy led to the creation of chicken pot pies. These make use of butchered chickens that did not come out perfectly and carrots that snapped off when digging them. An abundance of onions became French onion soup.

“When you have a kitchen, you have options. Imperfect or leftover products became items to stabilize the bottom line,” he says. A new and much larger wood-fired bread oven has been installed and the old bread oven is now a pizza oven. (A partnership with Shawnee Craft Brewing Company brought Apple Ridge’s distinctive wood-fired pizza to Scratch, at the Easton Public Market.) The kitchen enables sustainable farming; products get a new life and new use.

Apple Ridge also offers a line of its own specialty mustards, and a partnering beekeeper with on-site hives provides honey. Additionally, a former apprentice, Erik Sink, bases his fermentation business, Untamed Ferments, on the farm, offering kombucha, kimchi, and an assortment of krauts. A farm store operates daily, and teams of apprentices and employees attend 15 farmers markets each week during “green season.”

As a Certified Naturally Grown member—a grassroots alternative to organic certification from the USDA—Apple Ridge places a firm emphasis on healthful, nutrient-dense foods while adhering to high sustainable farming standards, including an efficient elimination of waste. And Bruno is always happy to discuss farm practices with inquisitive customers.

Scholl Orchards, Bethlehem and Kempton

Running a decades-old family business that grows peaches and apples so perfect-looking they resemble botanical illustrations might sound like an easy-peasy step-into-it job. But like most things, it’s complicated and challenging. While the Scholl Orchards farm store and two acres of apple orchards are located in Bethlehem, the family grows its iconic peaches, along with pears, plums, nectarines, cherries, and vegetables, across 70 acres in Kempton. Plenty of logistical planning goes into transporting products to the retail stand, along with, say, the Easton Farmers Market every weekend.

The orchard plot in rural Berks County was purchased by George Scholl in 1982. Ownership is unusual among farms, as many farmers rent all or some of their acreage. “The land is cheaper and the taxes are cheaper, but the retail money is elsewhere,” says George’s son Ben, 44, who runs the day-to-day operations with his brother Jake, 41. “We have to do bang for the buck. That’s the only way to survive in this business.”

Apple Ridge, weighs dough.

All the original, less productive trees have long been removed, and over the past 10 years the Scholls have planted between 15,000 and 20,000 trees. High-density apple planting using a wire trellis system—which means the trees don’t get huge—results in better production per acre and a better quality of fruit.

Last year Scholl Orchards went through the complicated process of hiring H-2A Visa agricultural workers from Mexico, who are housed on the farm. The four laborers from last year have returned, and a fifth person was added in 2024. “They came March 1 and they’ll go home December 1st,” says Ben. “These guys are like family to us now. They’re excited to be here and all they want to do is work.” Several regular part-time employees handle assorted chores and seasonal staff assist Sofia, Ben’s wife, who runs the farm stand.

Since neither Ben nor Jake has had any formal agricultural or business education, they’ve learned through “hard work and hard knocks.” A network of farmer friends also supplies support and suggestions. “We’re all on the same page; we all want to succeed,” Ben says.

Scholl Orchards maintains a good number of wholesale accounts in the Lehigh Valley, from roadside stands and Lafayette College to Meals on Wheels. They began to plant vegetables with assistance from a local Mennonite farmer.

Let’s talk about those fruit trees. They require some extra protection. Sustainable farming can only work when nature cooperates. Climate change has resulted in later spring frosts—deadly to delicate peach buds. It’s also prompted a major investment in four high-tech wind machines that pull down warm air into the orchard.

“It changes [the temperature] only a degree or two, but you can lose a crop over a half degree,” Ben says. A propane-fueled Frost Dragon tractor delivers warm air as the farmer drives in endless circles through the orchard all night.

Weather is one thing; pests are another, especially with our humid summers. The pleasure of fresh produce starts with eye-appeal, and insect-blemished fruit is a selling nonstarter. The Scholls practice Integrated Pest Management (IPM), which can disrupt insect mating cycles and get a boost from good insects like praying mantises and ladybugs.

While “value-added” is now vital currency in order to be sustainable, Scholl’s has famously been making fresh, unpasteurized apple cider pressed in Bethlehem since 1948. Shelf-stable house-brand condiments (salsa, ketchup, tomato spread, apple butter, pear butter, and peach butter) are prepared by a family business in Sassamansville. However, the biggest crowd pleaser may be its voluptuously textured applesauce. These products not only generate a year-round revenue stream but can utilize excess or less-than-perfect-looking produce.

After an arduous growing season, several cold months might seem like a relaxing respite from farming. Ben quickly disabuses that notion. “All winter long we’re pruning apple trees and fixing equipment, doing building maintenance, splitting and selling firewood,” he says. “There’s always something going on.”

Crooked Row Farm, Orefield

Growing up in the Lehigh Valley suburbs, Liz Wagner never envisioned a future in farming. After attending college in Philadelphia, she stayed there and found a position that utilized her degree in journalism. However, urban living and an office job began to feel claustrophobic. “I really loved exploring the city but missed the open spaces I had taken for granted as a kid,” says Wagner, 35. “I wasn’t homesick, but I wanted to be outside more.” So she began to consider other options.

Serendipitous events soon led her down a different career path. First, her parents decided to buy a parcel of land in rural New Tripoli, and build a home, and dedicate a few acres for farming. At that same time, Wagner was offered a yearlong internship on a Hudson Valley organic vegetable farm. Along with labor, she’d also be marketing produce at New York City’s Union Square Greenmarket twice weekly. She thought she might bring these agricultural skills back home to start a sustainable farming business. When Wagner ran this idea past her parents, they said, “Sure, give it a shot.”

By 2013, Wagner returned home and developed diverse agricultural and business skills before purchasing an Ore-field farmette with a well-established retail space in 2017. The two farmland locations, totaling nearly 10 acres, became Crooked Row Farm and Wagner joined a growing minority of woman-owned and operated farms. The business is certified organic, a time-consuming and expensive commitment that includes annual audits and records examinations. But Wagner wanted to adhere to principles learned during her apprenticeship. However, she supports growers who decline certification by noting that “the local farm economy trumps the growing practice priority.”

Sustainable Farming: Stocking a Farmstand with Local Products

The local farm economy gets a boost every time a farmer brings another grower’s produce into their sphere. There are a lot of products Wagner doesn’t grow or offer, but she recognizes their importance to her farmstand. So she reached out to local growers she knew. After starting with a couple of vendors, the list of trusted purveyors quickly expanded—including organic, noncertified but organically practicing, and traditional growers. Crooked Row’s farmstand now includes freshly baked bread from The Daily Loaf, meat, eggs, cheese, honey, kombucha, condiments, herbal teas, and more. Seasonality is key, so offerings vary.

While she has a small greenhouse in New Tripoli, two high tunnels were added in Orefield in 2020. The latter enable planting veggies directly into the ground. Because the structure gets warmer faster in spring and stays warmer longer into fall, her growing season extends closer to year-round. For example, hearty greens such as kale, lettuce, and spinach planted in October are harvested through April. Outdoor field crops include tomatoes, peppers, broccoli, and other vegetables. Several crops are locally processed into shelf-stable products such as ketchup, salsa, and pickles, all bearing a Crooked Row Farm label.

Family members maintain a consistent small presence in helping to manage and maintain the operation. Hired staffing, which fluctuated from year to year as Wagner figured out her needs, now consists of several part-time workers. “There are people I need to help me in the field with planting and harvesting, and I need people for the retail aspect in the stand. Some of the people will straddle those and switch off on different days, as I do,” she says. Because agriculture is considered a high-risk industry, field worker compensation insurance rates are much higher than for retail workers. Also, retail workers are trained to answer customer questions about products and practices.

In an industry where profit margins are extremely thin, economic sustainability comes down to “figuring out the right balance of production to labor,” such as how much Wagner can grow and stay within her labor costs, “and have enough product that everything is copacetic.”

First Friday events, held during varying afternoon hours at Crooked Row Farm market, put a festive spin on shopping with featured products that run the gamut from grain-fed beef from Gauker Farms to Cellar Beast Winehouse selections.

Imagine, then, a world in which farms are producing and/or offering enough to set the table for an entire meal. Each choice counts; each product you purchase can make a difference.

The High Costs of Sustainable Farming, Deconstructed

When you shop at farmers markets, you might wonder how the farmers calculate costs. We’ve looked at three common products and have asked our farmers to help us understand the factors that impact cost.

Apple Ridge Farm: 1 dozen eggs, $9

Organic day-old chicks with beaks and toes intact are purchased and shipped in early winter. There’s usually a little bit of loss during that process, so the investment is about $15 a bird even before it lays its first egg, which takes five months. (Bruno must factor in ongoing losses from predators such as hawks and foxes.) Nutrient-dense organic feed, purchased from Panorama Organics in Oley, is expensive and supplemented with whatever the chickens forage. People are paid to feed and move the birds, wash the eggs, place them in cartons, refrigerate them, and transport them to markets. The light-driven birds, moved to a barn over the winter, molt their feathers, stop laying eggs, and stock up on calcium. In spring, feathers regrow and egg laying restarts.

Scholl Orchards: 1 quart of peaches, $8

It takes a peach tree 2 to 4 years to produce fruit. When the peaches finally arrive, they are hand-picked and hand-packed. They are always presented to consumers as tree-ripened, which is a more laborious process that requires more skill and care in packing—they also need to withstand the journey from Kempton to Bethlehem, and beyond. Unlike grocery stores where the fruit is shipped green and then customers rummage through piles of fruit that get bruised in the process, these well-cared-for peaches look, aptly, like nature’s perfect gifts from the tree.

Crooked Row Farm: 1/3 pound bag baby lettuce salad mix, $4

Input costs for salad mix include higher-priced organic seeds, and disease-resistant varieties cost even more. Seeds are started in organic peat mix and heat mats keep them from getting too cold. Salad greens are cut and triple-washed in a stainless steel sink—in a completely sanitized washroom—before drying in a spinner. This labor-intensive product is then weighed and packaged in compostable plastic bags (more expensive but more environmentally friendly) before being stored in the walk-in cooler and display fridge.